- Dwelling On It

- Posts

- When Policy Outpaces Capacity

When Policy Outpaces Capacity

The human cost of reform in an over-stretched housing system.

There's a meeting happening right now in a housing association somewhere in England. The agenda looks familiar: Awaab's Law compliance, building safety updates, Decent Homes Standard preparations, net zero planning, complaints performance, staff vacancy rates.

Someone asks how they're supposed to deliver all of this with the same team that was struggling to meet last year's targets. There's an awkward silence. Someone mentions "working smarter." Someone else talks about "prioritisation." Everyone knows these are just polite words for an impossible situation.

This is the reform paradox: Every new policy arrives with good intentions and solid justification. But good policy does not automatically create the capacity to deliver it.

Right now, social housing providers are absorbing Awaab's Law timelines, new Consumer Standards, an expanded Decent Homes Standard, the Net Zero 2050 trajectory, and mounting Building Safety obligations all layered on top of day-to-day operational pressures that were already stretching teams to breaking point.

Each reform, taken individually, is defensible. Each addresses a real problem. Each reflects lessons hard-learned from tragedies and systemic failures. But together, they create what one housing director recently called "a perfect storm of accountability" a situation where the volume of requirements has fundamentally exceeded the sector's capacity to deliver them well.

The question isn't whether these reforms are necessary. It's whether anyone seriously accounted for what it would take to implement them all simultaneously.

The Mathematics of Overload

The numbers tell a stark story about capacity erosion:

Recent research on London housing associations found that patch sizes have increased to up to 1,000 households per staff member, with frustration and stress exacerbating staff shortage and turnover rates.

UNISON's Housing Worker Survey 2024–25, based on over 1,100 responses, reveals that 77% of housing staff describe their work as stressful, with four in five saying pressures have worsened in recent years. Nearly a third manage patches of more than 1,000 homes, and 45% say they lack the training needed for their jobs.

A quarter of housing workers reported taking time off due to stress, and over half of employers are struggling to fill roles.

These aren't abstract workforce statistics. They're people trying to inspect properties within 14 days of a hazard report while also managing 1,000 other homes, preparing for regulatory assessments, and implementing new compliance frameworks they haven't been trained on.

The statutory duties facing social landlords have effectively doubled in under a decade. Each new requirement demands:

Data infrastructure to evidence compliance

Skilled staff to interpret, manage, and respond

Funding to retrofit, repair, and remediate

Governance capacity to oversee and assure

Yet staffing levels, contractor capacity, and funding lines have not grown at remotely the same pace.

When staff are overburdened, high turnover rates undermine the ability to understand issues and handle them properly, leading to poor reporting and reactive rather than proactive approaches.

Reform Without Resources: The Funding Reality

Awaab's Law was designed to prevent another tragedy. The Decent Homes Standard aims to ensure basic quality. Building safety regulations respond to Grenfell. These are all morally essential reforms.

But here's what the sector faces financially:

The cost of retrofitting social homes to net zero is estimated at £104 billion across roughly five million social homes in the UK, with individual property costs ranging from £2,500 to £50,000.

The £3.8 billion decarbonisation fund promised represents only 4% of the estimated £104 billion needed.

The National Housing Federation has called on the government to confirm an additional £3.7 billion in funding for social landlords by 2030 to meet the new Decent Homes Standard requirements.

The NHF is calling for £5 billion in total investment by 2030 to continue funding the Warm Homes: Social Housing Fund.

Most new requirements arrive without proportionate uplift in baseline funding or transitional support. The expectation is transformation. but through existing teams, systems, and contractors already stretched impossibly thin.

The result is predictable:

Teams firefighting instead of planning

Compliance overtaking improvement

Performance data chasing the tail of real risk

The language of "continuous improvement" becoming hollow when staff are simply trying to keep up

The Human Bandwidth Crisis

Behind every compliance line and KPI is a person trying to make sense of it all.

Managers can spend up to 80% of their time dealing with staffing issues, leaving limited capacity for quality-focused initiatives. Research found that 75% of managers worked beyond their contracted hours to fill gaps caused by staffing shortages, with many reporting symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Anecdotally, managers speak of policy fatigue. Surveyors working evenings to clear inspection backlogs. Data teams caught between regulators demanding transparency and systems incapable of producing it.

This isn't just an operational challenge, it's a wellbeing crisis with serious consequences for service delivery.

When staff are overburdened and fatigued, the quality of care they provide naturally suffers. Although workers strive to deliver compassionate service, the demands of covering additional shifts and tasks compromise the ability to offer individualised, high-quality work.

When reform outpaces capacity, we create the conditions for burnout and error, the very risks regulation seeks to prevent. We're asking people to run faster on a treadmill that's already at maximum speed, then expressing surprise when they stumble.

The Ripple Effects

The capacity crisis doesn't just affect housing staff. It ripples outward:

Contractors are overwhelmed. The supply of skilled trades has declined significantly, making it harder to meet Awaab's Law timelines or complete building safety works on schedule.

Residents wait longer. Analysis shows that satisfaction is more strongly linked to whether repairs are completed within target timeframe than to the number of emergency repairs carried out. When capacity is stretched, targets get missed, and satisfaction plummets.

Quality suffers. When teams are in permanent crisis mode, the focus shifts from doing work well to simply getting it done. Corners get cut. Documentation slips. The very compliance you're trying to achieve becomes harder to evidence.

Innovation stops. There's no bandwidth for thinking differently, testing new approaches, or learning from what works elsewhere. Everything becomes about survival.

The Deeper Problem: Policy as Performance

Here's an uncomfortable truth: Some policy reform is driven less by realistic assessment of what's achievable and more by the need to be seen doing something.

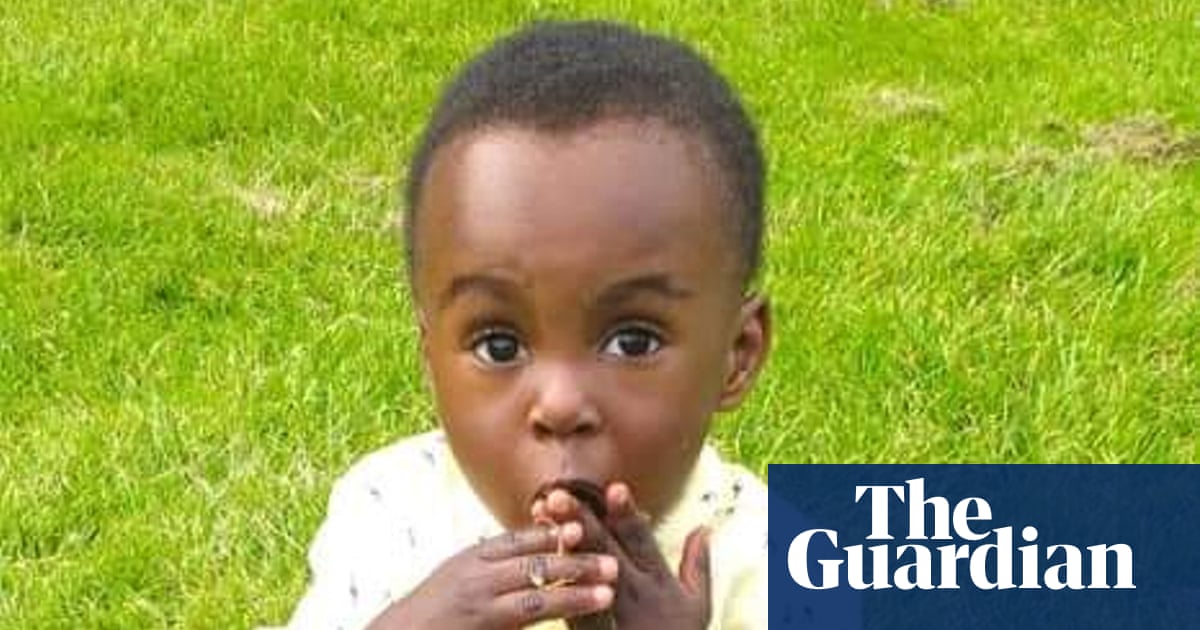

After Grenfell, after Awaab Ishak, after every high-profile failure, there's understandable pressure to act decisively. New legislation, new standards, new requirements.

But if those requirements aren't matched with realistic timeframes, adequate funding, and workforce development, they become what one practitioner called "symbolic policy" measures that look decisive but can't actually be delivered at the pace or scale demanded.

The sector then faces an impossible choice: admit they can't comply (and face regulatory sanction) or pretend compliance is achievable (and burn out staff trying to deliver the impossible).

Neither option serves residents well.

What Sustainable Reform Looks Like

The way through this isn't to abandon reform. It's to design policy that acknowledges human and organisational capacity as real constraints, not obstacles to be overcome through willpower.

Synchronise Implementation Timelines

Stop layering new requirements on top of half-implemented previous reforms. Give organisations time to embed one major change before introducing the next. Staggered implementation isn't weakness, it's realism.

Fund the Transition, Not Just the End State

Meeting new standards requires investment in:

Staff training and development

System upgrades and data integration

Temporary additional capacity during transition periods

Contractor workforce development

Without this transitional funding, you're asking organisations to transform while maintaining business as usual, a recipe for failure.

Build Skills Pipelines

Research found that retrofitting homes in the North of England could create 77,000 new jobs in the region by 2035 but only if we invest in training those workers now. The same logic applies across all the skilled trades and professional roles the sector needs.

Prioritise Core Compliance Before New Pilots

Before launching another innovation programme or strategic initiative, ask: can teams actually deliver their core compliance and safety responsibilities? If not, new programmes are just adding to overload.

Many landlords and local authorities are grappling with identical challenges. Shared approaches to contractor frameworks, data standards, and compliance reporting could reduce duplication and spread best practice.

Use Data Integration to Cut Duplication

The goal of better data shouldn't be more reporting , it should be smarter working. Integrate systems so teams can see the full picture without entering information multiple times or producing endless bespoke reports.

The Argument for Breathing Room

Encouragingly, where housing associations have invested in specialist functions, like dedicated rent collection officers, performance has improved, with major urban local authorities seeing arrears fall by 18.5% between April 2024 and April 2025.

This shows what's possible when capacity matches ambition. When staff have the time, training, and resources to do their jobs well, outcomes improve for everyone.

But right now, most organisations are in the opposite situation being asked to do more and more with less and less.

The most sustainable reform is the kind that allows people to breathe to understand new requirements, embed them properly, and improve gradually before the next wave arrives.

Because policy written in haste often lands on inboxes already full. And when that happens repeatedly, something has to give. Usually, it's either service quality or staff wellbeing. Often, it's both.

The Path Forward

Progress in housing will always depend on change. We can't freeze policy at some ideal equilibrium point. The world shifts, standards evolve, new challenges emerge.

But we can design reform that recognises capacity as finite and human limits as real.

That means:

Honest conversations about what's achievable within what timeframes

Adequate resourcing matched to the ambition of reform

Workforce development that creates the skills pipeline we need

Implementation support during transition periods

Learning loops that adjust policy when capacity constraints become evident

It also means accepting that sometimes the right answer is "not yet" that delaying implementation to build capacity first produces better outcomes than rushing forward regardless of readiness.

The Human Stakes

At the core of this issue are people. Housing staff trying to serve residents well despite impossible workloads. Residents waiting for repairs that teams can't get to fast enough. Contractors stretched across too many jobs. Boards trying to govern organisations under unprecedented pressure.

Every new policy requirement is someone's inbox, someone's evening working late, someone's stress about whether they're doing enough to keep people safe.

When we design policy without accounting for the humans who'll implement it, we're not just creating operational challenges. We're creating conditions for failure and potentially for the very tragedies policy reforms were meant to prevent.

Reform that ignores capacity risks breeding cynicism and burnout. Reform that recognises capacity builds resilience and sustainable change.